Researchers have found promising hints that the atmosphere of a distant planet contains gases linked to life, BBC reports today. A team led by University of Cambridge astronomer Nikku Madhusudhan reports in The Astrophysical Journal Letters that it used NASA’s JWST telescope to detect the signatures of the gases dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) in starlight that had passed through the atmosphere of K2-18b, a massive planet 120 light-years from Earth. On Earth, those gases are produced by marine phytoplankton and give sea air its distinctive scent.

The results will provoke intense interest in the planet but are a long way from definitive proof that it is inhabited. That’s because there is still a possibility that the detected signature—an extremely tricky measurement to make—is an instrument artifact. It’s also possible that DMS and DMDS are produced on the planet by some nonbiological process. Last year, a different team of researchers reported signs of DMS within the dust and gas of the definitively lifeless comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, calling into question the gas’ usefulness as a biosignature.

“If we want to rely on such simple molecules as biomarkers, then you need all the information you can possibly get,” Nora Hänni, the University of Bern chemist who led the comet analysis, told Science last year.

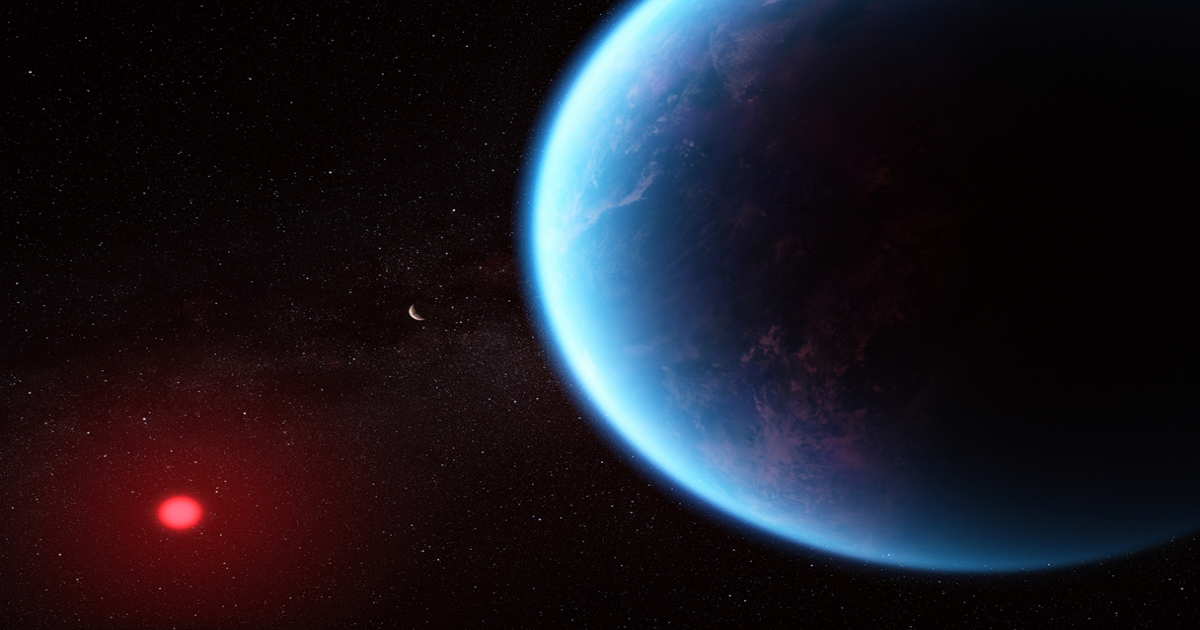

K2-18b would normally be considered an unlikely candidate for extraterrestrial life because it is very dissimilar to Earth, the only planet known to harbor living organisms. The planet is 2.6 times the size of Earth and 8.6 times as massive, putting it closer to a gas giant like Neptune than a rocky planet like ours. Discovered in 2017, the so-called sub-Neptune drew interest in 2019 when observations detected water vapor in its atmosphere. The following year, a modeling study suggested it could have habitable conditions on its surface, if it has one.

In 2023, a team also led by Madhusudhan detected carbon-based molecules methane and carbon dioxide in its atmosphere, along with the merest whiff of DMS. At the time, the researchers suggested K2-18b could have a planet-spanning liquid water ocean and a thick hydrogen-dominated atmosphere, declaring it a “hycean” world—a mashup of “hydrogen” and “ocean.” Many researchers were skeptical of the reported DMS signal, but the same team now reveals a stronger DMS signal, as well as possible traces of DMDS. The researchers say they should be able to confirm the detection with an additional 16 to 24 hours of time on the JWST.

Even then, researchers say there should be a very high bar for claiming the presence of life based solely on the gases in a planet’s upper atmosphere. “Everything we know about planets orbiting other stars comes from the tiny amounts of light that glance off their atmospheres,” Oliver Shorttle of Cambridge told BBC. “So it is an incredibly tenuous signal that we are having to read, not only for signs of life, but everything else.”

Researchers would prefer a more thorough knowledge of the planet’s atmosphere and surface to exclude other possibilities. “On Earth [DMS] is produced by microorganisms in the ocean, but even with perfect data we can’t say for sure that this is of a biological origin on an alien world because loads of strange things happen in the Universe,” Catherine Heymans of the University of Edinburgh and Scotland’s Astronomer Royal told BBC. “We don’t know what other geological activity could be happening on this planet that might produce the molecules.”

Christopher Glein, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, posted a preprint on arXiv on Sunday suggesting K2-18b may host a vast magma ocean wrapped around a large rocky core—a very different beast from the water-world idea that Madhusudhan’s team advocates. Glein told The New York Times it would take a lot to persuade him there’s life on the planet: “Unless we see E.T. waving at us, it’s not going to be a smoking gun.”