A British artist claims to have replicated in paint a colour that scientists say they discovered by having laser pulses fired into their eyes.

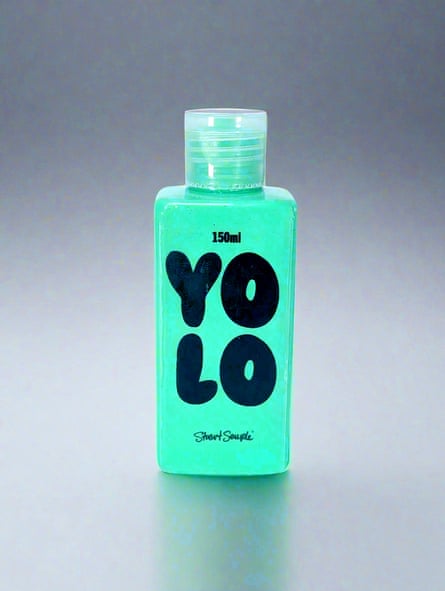

Stuart Semple created his own version of the blue-green colour based on the US research published in Science Advances, which he is selling on his website for £10,000 per 150ml jar – or £29.99 if you state you are an artist.

In the experiment conducted at University of California, Berkeley, a laser was used to stimulate individual cells in the retinas of five researchers, pushing their perception of colour beyond its natural limits.

Before creating ‘yolo’, Semple formulated what he claims are the world’s blackest and pinkest paints. Photograph: Stuart Semple

Semple, who has previously made what he claims to be the world’s blackest and pinkest paints, synthesised his version of the colour in a more low-tech manner.

The artist mixed pigments, adding fluorescent optical brighteners that absorb ultraviolet light and re-emit it as visible blue light, making materials appear whiter or brighter. Using a spectrometer, which separates light into its constituent colours, he then analysed their intensity to best match his paint samples to the target hue.

“I’ve always thought that colour should be available to everybody,” said the artist, who also produced his own version of Yves Klein’s famous ultramarine blue paint. “I’ve fought for years to liberate these colours that are either corporately owned or scientists have staked a claim to, or have been licensed to an individual person.”

The scientists named the colour olo. Semple, who called his version yolo, has form for irreverently reproducing colours only available to an exclusive few.

When the artist Anish Kapoor bought the exclusive rights to the world’s blackest paint, Semple made what he said was a blacker one and banned the Turner prizewinner from using it.

Humans perceive the colours of the world when light falls on colour-sensitive cells called cones in the retina. There are three types of cones that are sensitive to long (L), medium (M) and short (S) wavelengths of light.

Red light primarily stimulates L cones, while blue light chiefly activates S cones. But M cones sit in the middle and there is no natural light that excites these alone.

The Berkley experiment produced a colour beyond the natural range of the naked eye because the M cones are stimulated almost exclusively. Its name olo comes from the binary 010, indicating that of the L, M and S cones, only the M cones are switched on.

Semple believes that colour should be available to everybody, rather than just an exclusive few. Photograph: Stuart Semple

Semple said: “I think they’ve triggered an experience in people that they’re approximating to a colour. What I’ve done is tried to make an actual colour of that experience.”

Austin Roorda, a vision scientist on the Berkeley team, said he would buy a bottle of the paint, but not for £10,000. “I might even commission my cousin who’s an artist to do some work with this paint,” he said.

“It’s impossible to recreate a colour that matches olo,” he added. “Any colour that you can reproduce would just pale by comparison. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a paint or a swatch of colour or something or even a monochromatic laser, which generate the most saturated natural human colour experiences.”

The scientist said he had also tried to recreate the colour by meticulously mixing two liqueurs: the slightly sweet melon-flavoured Midori and Blue Curaçao, made from the dried peel of the bitter orange.

“It’s a bit foul, Roorda said of the concoction’s taste. “But the more I drink, the more it looks like olo.”