The path to Kilmar Abrego García’s deportation to a notorious megaprison in El Salvador began six years ago, when a suburban Maryland police detective typed a critical allegation into a Gang Interview Field Sheet.

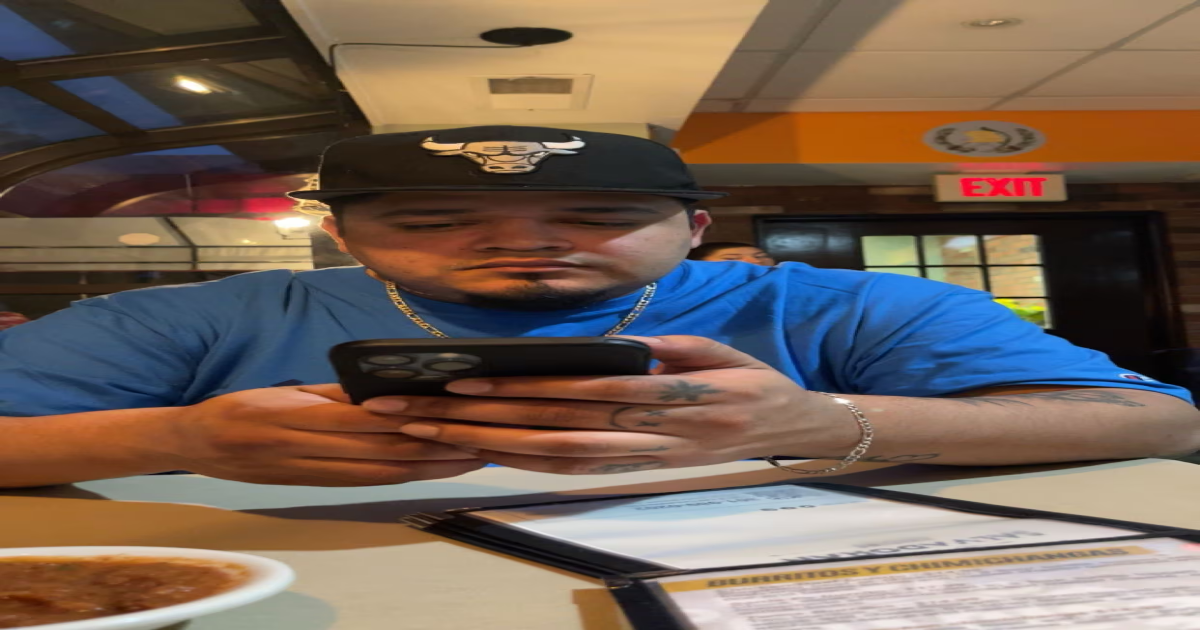

“An active member of MS-13 with the Westerns clique,” wrote the detective in 2019, after detaining Abrego García at a Home Depot in Prince George’s County while he stood in the parking lot looking for construction work. His proof: an unnamed confidential informant and Abrego García’s Chicago Bulls cap, which the officer wrote in his report was “indicative of the Hispanic gang culture.”

The allegations in that report — vehemently disputed by Abrego García’s family and attorneys — have become central to the government’s reasoning for deporting him in an escalating legal battle between the Trump administration and the judicial branch. That case alleges federal officials violated the man’s due process rights when they deported him last month to the Salvadoran government’s Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT), despite an immigration judge’s order expressly barring that.

Yet federal officials are bucking a Maryland District Court judge’s orders to facilitate Abrego García’s return — and have launched a full-throated effort outside of court to label him a gang member, a “terrorist” and a “human trafficker.”

“Abrego García is an illegal alien MS-13 gang member and foreign terrorist,” Trump said during a White House news briefing Friday, citing a dossier on Abrego García his administration has widely circulated during the past week. “This is the man that the Democrats are wanting us to fly back from El Salvador to be a happily ensconced member of the USA family.”

To date, the only evidence federal authorities have produced to support such allegations is the Maryland police detective’s 2019 gang sheet.

But a Washington Post review of court documents and other public records found that attorneys and judges have questioned the integrity of the allegations in that document since it was written.

The detective who filled out the gang sheet — Ivan Mendez — was suspended from the Prince George’s County Police Department days after detaining Abrego García because he’d been accused of tipping off a sex worker he had hired about an ongoing investigation into a brothel she ran. He was later criminally indicted and fired after pleading guilty to misconduct in office, one of several members of the gang unit who were criminally prosecuted. Mendez did not respond to messages seeking comment.

The gang unit in Prince George’s County, whose residents are majority Black and Latino, stopped using the Gang Field Interview Sheet as a source of intelligence gathering about three years ago, amid a civil lawsuit that alleged young men of color were disproportionately represented in it.

And in January, federal officials in the Washington region decommissioned GangNET, a database of alleged gang members that those field sheets fed into, because participation drastically tapered as its credibility came into question.

Lucia Curiel, an attorney who represented Abrego García after the 2019 encounter, said he fled gang threats in El Salvador as a teenager and had no contact with police before the Home Depot arrest. If not for Mendez’s allegations, she said, Abrego García would not have been on ICE’s radar.

“It’s the direct through line to what’s happening today,” Curiel said. “All the evidence, or lack thereof, suggests this is the single source of the allegation, and the allegation is the single reason he was deported and sent to CECOT. The two agencies to blame are the Trump administration and the Prince George’s County Police Department.”

The Prince George’s County Police Department has long faced allegations that the agency’s tactics targeted Black and Latino people.

From 2004 to 2009, the department was placed under federal oversight after the agency was investigated for canine unit brutality and shooting more people than any other police department in the country. A group of Black and Latino officers sued the department in 2018, alleging police leaders discriminated against officers of color and enabled racist behaviors that harmed residents.

Last year, the department was sued again over the gang unit and its use of the GangNET database after community members repeatedly complained that officers were racially profiling young Latino men and incorrectly labeling them as gang members.

The department began participating in the database in 2012, after receiving a multimillion-dollar federal grant from the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, known as HIDTA, which hosted and maintained it.

The county had developed a Gang Field Interview Sheet to collect information on suspected gang affiliates, said a former member of the gang unit who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Officials from HIDTA, which coordinates task forces between local and federal law enforcement to combat drug trafficking, trained county officers on the federal codes and regulations guiding the database. The gang unit detectives did not have the power to directly enter data into GangNET, the former gang unit member said, but the information came directly from their field reports with no built-in vetting.

The gang unit was incentivized to fill the database, said the former member, because intelligence gathering was a core function of the grant funding.

When the gang unit’s leadership changed in the mid-2010s, the officer said, standards fell.

Expectations shifted to “you better be submitting names, or you won’t last in the gang unit,” the officer said, citing conversations with other gang unit members. “If you’re not submitting names, then your career, your time in that unit is very limited.”

Some officers in the gang unit lacked cultural understanding, the officer said, and Latino residents were “looked at a certain way.” If someone wore “a certain type of clothing” or had a “certain type of tattoo,” he said, “they were going to get … stopped and then interviewed and then put in the system.”

Attorneys representing those apprehended by the gang unit saw those patterns.

Curiel said she and her colleagues at Amica Center for Immigrant Rights — who were representing people in deportation proceedings — realized nearly a dozen cases started the same way. Young men, some of them teenagers, were stopped by police but rarely charged with a crime. A member of the Prince George’s County gang unit — often Mendez — would fill out a Gang Interview Field Sheet, she said. Then, local officers would notify ICE.

Curiel flagged her observations to the immigration advocacy group CASA, which notified the county council’s only Latino member at the time, Deni Taveras.

Together, they began campaigning for transparency around the database, an effort that Curiel took to court when she was asked in the spring of 2019 to represent a man named Kilmar Abrego García.

On March 28, 2019, Abrego García drove to a Home Depot in Hyattsville, Maryland, and stood outside the day laborer’s entrance looking for work.

Three other Latino men in their 20s were already there, according to police records. Abrego García did not know them well, his attorneys said.

A Hyattsville Police Department detective approached the others in the group. Within minutes, members of the Prince George’s County police gang unit arrived — and put all of them, including Abrego García, in handcuffs.

An incident report from Hyattsville police names the other three men, but not Abrego García, and says the detective approached them because he saw members of the group “stashing something underneath a car” in the parking lot — which Mendez later said were small plastic bottles containing marijuana. The Hyattsville report makes no mention of suspected gang activity.

The field interview sheet — the only record Prince George’s police claims it has from that day — offers a different narrative.

Mendez wrote that the Hyattsville detective had recognized a man in the group as a member of the MS-13 Sailors clique. That man, court records show, was on probation at the time after being convicted of misdemeanor assault and participating in gang activity, charges that had stemmed from a fight at a shopping mall. Another man was labeled a high-ranking gang member because of a tattoo featuring horns, and Mendez called a third man a potential recruit because he was standing nearby.

Abrego García, Mendez wrote, had been identified by an unnamed confidential informant as an “active member” of MS-13’s Western clique in Upstate New York — a place he has never lived. Mendez cited Abrego García’s clothes as further proof, including a hooded sweatshirt that featured green bands covering the eyes, ears and mouth of Benjamin Franklin’s face as printed on the $100 bill. His wife, Jennifer Vasquez Sura, would later say she bought him the sweatshirt — for sale on FashionNova — because she liked the design.

While all four men were detained and questioned, none were ever charged with a crime, according to court documents.

During hours of questioning, Abrego García repeatedly denied gang membership, according to court documents. Prince George’s police officers told Abrego García that he would be released if he provided information about other gang members, according to his attorney, but he could not because he did not have any.

Then police handed Abrego García over to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, who arrested him for being in the country illegally.

A month later, at Abrego García’s bond hearing before Immigration Judge Elizabeth Kessler, a Justice Department attorney argued that he was a flight risk and public safety threat — citing solely the allegations in Mendez’s report.

The government attorney also submitted a federal form claiming Abrego García and one of the other men at Home Depot had been “detained in connection to a murder investigation.” The Post could find no mention of a murder investigation in any other public records, and Prince George’s County police did not respond to questions about other investigations involving Abrego García or the agency’s Gang Unit.

At the hearing, Kessler noted that discrepancy — expressing reservations about the strength of the evidence linking Abrego García to gang activity.

“I am not particularly concerned about the conclusions that there may be an indicia of gang membership from clothing,” she said, according to a transcript of the hearing. “The respondent can certainly wear whatever he wants in this country and I will be reluctant to place any weight on that.”

Still, Kessler said she was “very seriously concerned” by the sheet filled out by Mendez and ultimately denied Abrego García bond.

For the next three months, Abrego García sat in ICE detention.

At his August 2019 deportation hearing, Abrego García and Vasquez Sura — who had married through a glass partition at the ICE detention center — testified for two days before Judge David M. Jones, a Trump administration appointee.

Abrego García told the judge that as a teen in El Salvador, the Barrio 18 gang attempted to extort his mother’s pupusa business, then recruit him and his brother into their ranks — threatening to kill them if they didn’t join.

When given the chance to make their case regarding Abrego García’s alleged gang ties, the federal government produced just one piece of evidence: the Prince George’s County gang field interview sheet.

Curiel’s own attempts to question the gang unit officers were thwarted.

The county police department’s inspector general told her Mendez wasn’t available because, just days after Abrego García’s detention, he had been suspended regarding the sex worker investigation. Other gang unit officers declined to discuss Abrego García’s case unless compelled by a judge. The Hyattsville detective, Curiel said in court papers, never returned her calls.

In his Oct. 10 ruling, Jones granted Abrego García withholding of removal, a protection available to migrants who face likely persecution or harm if returned to their country. Jones did not comment on the government’s allegations that Abrego García was a gang member but said his testimony about safety fears was credible.

The ruling was rare for the former military judge, who has an above average denial rate for asylum cases, according to court data. Federal officials under the first Trump administration did not appeal.

On Oct. 23, 2019, Abrego García was released from custody and ordered to check in with ICE annually. Records reviewed by The Post show he fully complied.

Shortly after his release, the Prince George’s County Council voted unanimously to bar all county agencies from engaging in immigration enforcement.

Five years later, Abrego García was driving in Prince George’s with his 5-year-old autistic son when he was pulled over by ICE officers.

Abrego García called his wife on speakerphone, she said, and agents told Vasquez Sura she had 10 minutes to pick up their son or he would be turned over to Child Protective Services. When she arrived, ICE officers said his immigration status had changed and asked if she wanted to say goodbye. Abrego García was crying.

The next day, on March 13, he called her from detention in Louisiana and said ICE agents had showed him photos they’d secretly taken of him at a restaurant and basketball court, asking him to identify people in the background. But Abrego García said he didn’t know them.

On March 15, from a Texas detention center, Abrego García called his wife again in a panic. He was being deported to El Salvador.

Vasquez Sura hired two new attorneys: one in El Salvador, who could find no criminal charges pending there, and one in Maryland, who filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court.

The judge overseeing that case, Paula Xinis, has repeatedly ordered the Trump administration to facilitate Abrego García’s return — a ruling largely affirmed by a federal appeals court and the U.S. Supreme Court. The government’s gang allegations, Xinis said in one ruling, are unsubstantiated.

The Trump administration has turned to the court of public opinion.

This week, Attorney General Pam Bondi released what she described as evidence of Abrego García’s MS-13 ties, all of it based on the Prince George’s Gang Field Interview Sheet. The Department of Homeland Security unearthed and posted to social media a court petition Vasquez Sura filed against Abrego García in 2021 that stated he struck her during an argument, saying it proved he was violent.

Vasquez Sura, who never followed up on the petition, said the altercation stemmed from the emotional and psychological trauma her husband experienced during the 2019 ICE detention. “Kilmar has always been a loving partner and father,” she said, “and I will continue to stand by him and demand justice for him.”

As proof of their allegations that Abrego García is a “human trafficker,” Trump officials also released a DHS investigative report regarding a 2022 traffic stop in Tennessee — which also cites the Prince George’s gang allegations. It wasn’t immediately clear when the report, which has no date but appears to have been printed on Thursday, was produced.

It alleges that Abrego García was pulled over for speeding by a Tennessee Highway Patrol trooper, according to the report. He told the trooper that the seven other men in the van, owned by his boss, were fellow construction workers he was driving from Texas back to Maryland.

The trooper, according to the DHS investigative report, said a lack of luggage in the van made him suspect potential labor trafficking. The trooper ran his name and saw an instruction to notify federal authorities, according to the Tennessee Highway Patrol. But federal officials who were contacted said there was no need to detain him, the agency said, and Abrego García was issued a warning for driving with an expired driver’s license and released. No other charges were filed.

On Thursday, the U.S. Court of Appeals excoriated the Trump administration.

“The government is asserting a right to stash away residents of this country in foreign prisons without the semblance of due process that is the foundation of our constitutional order,” the appeals court wrote. “The government asserts that Abrego Garcia is a terrorist and a member of MS-13. Perhaps, but perhaps not. Regardless, he is still entitled to due process.”

Steve Thompson, Maria Sacchetti and Jeremy Roebuck contributed to this report.