Finally — the long-hidden paragraph. The one on Page 3 of a 1958 FBI memo, a document so secret it is literally stamped “SECRET,” the word tilted as if the person were rushing to stash the record in some government basement, perhaps in a vault behind a gantlet of levers and dials.

On Tuesday, with the release of more John F. Kennedy assassination records from the National Archives, that little paragraph rose from the dust. We already knew the government was opening the mail of American citizens. But it turns out the CIA had as many as 300 of its employees engaged in various aspects of its mail “coverage” operation — which included reading Lee Harvey Oswald’s letters — at a cost of $1 million a year.

It was just one passage in one government document among a seemingly endless number that, since the 1990s, have been dumped into the chasm of Kennedy narratives and assassination theories. But why were details about the scope of the CIA’s mail-snooping program withheld all these years? Do these revelations — and countless puzzle pieces like it — tell us who killed Kennedy? Or do these morsels merely offer more context and loose threads about America’s secret government?

Maybe, it’s something in between.

These records are by no means easy to peruse or absorb. The font is faded. The type is small. Strange pen marks slash through words. It’s not like the National Archives, CIA or FBI supplement each page with a guide explaining the identities of the people mentioned. And with each new release, it takes a bit of technological know-how to determine which parts of which documents are fresh.

Still, historians barrel forward with the hope that a pulled thread will loosen and unravel the most guarded secret in American history. (Edit: One of the most. Aliens. That’s another biggie.)

Jefferson Morley, a former Washington Post editor and reporter, is one such Kennedy scholar. He’s been studying the Kennedy files for years and wrote an expansive biography in 2017 on James Angleton, the CIA’s counterintelligence chief who’d been tracking Oswald before Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

On Thursday, Morley published a startling conclusion on the Substack page that he edits, JFKFacts: “The fact pattern emerging from the new JFK documents shows that: A small clique in CIA counterintelligence was responsible for JFK’s assassination.”

Later that night, he elaborated during a public Zoom call with followers and Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-Fla.), the chairwoman of the House Task Force on the Declassification of Federal Secrets. Luna, who announced that Morley will testify at an April 1 task force hearing, said she was searching the tranche of National Archives records for a “CIA whistleblower report” from the agency’s inspector general’s office that “implicated the CIA in the assassination of JFK.”

The Post contacted the CIA’s office of public affairs Friday morning and is awaiting a response.

If the people mentioned in that report are still alive, Luna said, she’d like them to testify before Congress.

Morley’s chief interest continues to be Angleton — the protagonist of his years-long book investigation, a man who spent his career hunting for CIA officers secretly working for the Soviets.

“I’m not saying that [Angleton] was the mastermind of the assassination. But he was the mastermind behind Oswald,” Morley said Thursday night during his open Zoom call. “The failure of Angleton to intercept or do anything about Oswald at the same time that he’s running operations around him — that combination, yes — that tells me Angleton played a complicit role in Kennedy’s assassination.”

As Morley began scanning this week’s release, he happened upon numerous records that fed his interpretation of the case.

One is that FBI correspondence from 1958 — the memo about the CIA’s mail “coverage” program. Written by A.H. Belmont, a now-deceased senior bureau official, the letter describes how the FBI recently learned that Soviet “illegal agents” worldwide were required — if they wanted to meet their principal — to send “proper communication” to “K.S. Smirnov, Central Post Office, Vladmir, U.S.S.R.” In response, the FBI inquired with the U.S. Postal Service to gauge the feasibility of cracking open mail going to the Soviet Union.

Around the same time, in January 1958, Angleton reached out to an FBI contact. The CIA man had gotten wind of the FBI’s inquiries with the Postal Service and wanted to tell him something secret — something that could get him fired at the agency, according to the memo.

So, Angleton told the FBI official that the CIA already had a mail interception program up and running, its sole purpose being to identity potential recruits behind the Iron Curtain with possible ties to the U.S. He told the bureau official that the program operated out of New York and involved “an elaborate array of IBM machines to tally and tabulate the results,” according to the FBI memo summarizing what Angleton had said.

Then, the bureau memo cited Angleton’s figures that had not been revealed until this latest National Archives release — that the hundreds of CIA personnel were “exclusively engaged on various facets of the coverage” and that the cost of the operation was “well over a million dollars a year.”

The office letter goes on to describe some of the CIA’s process — how initially envelopes were photographed, but the envelopes were not to be opened. And then, the FBI memo reveals information that had been hidden until now: “The envelopes were microfilmed and the names and addresses appearing thereon were indexed with IBM equipment. Several months ago CIA began opening some of this mail, microfilming the contents and indexing pertinent data therein. Approximately 250,000 names have been indexed by CIA.”

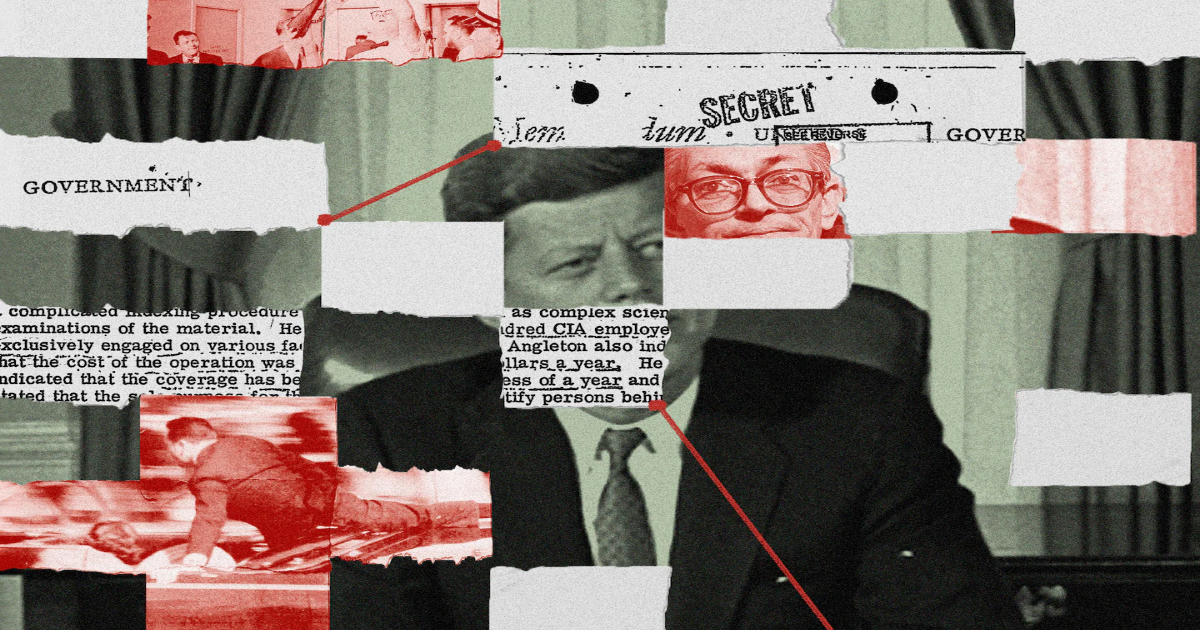

Photos of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

Morley had previously studied the CIA’s mail eavesdropping program, which ran from roughly 1956 to 1973 and inspected the letters between Oswald and his mother when he was living in the Soviet Union for two-plus years. But even he was surprised by the operation’s magnitude — a scale that suggests to him that the agency’s surveillance of Oswald before the assassination was part of a concerted and broad effort to recruit Americans living or traveling in the Soviet Union as spies.

“I always envisioned it as one office in New York. But this just goes to show that it was bigger than anyone ever knew,” he said. “A million dollars in 1958? That’s got to be more than $10 million now. And 200 or 300 people working on it? Maybe Angleton was bragging. We have to be cautious.”

Though the American public has long known about the agency’s mail interception program against Americans, Morley understands why the government held back those figures for so long.

“I take the government at its word. If they keep something secret for 60 years, they’re saying it’s sensitive,” Morley said. “That’s what they’re telling us, and we should believe them.”