Hands down, Ryan Coogler’s 1930s-set crime film/historical thriller/vampire horror-show Sinners is one of the best movies of 2025 so far. The Black Panther and Fruitvale Station director has made a project that’s simultaneously audacious and personal, the kind of big-swing original story that cinephiles are always clamoring for around the edges of the endless franchise movies, reboots, prequels, sequels, and spinoffs that dominate American studio output. It’s about what the American dream has looked like for Black citizens across the past century. It’s about Coogler’s own family history and his relatives’ relationships with everything from bootlegging to early Black-owned businesses to blues. It’s a great watch. It’s also a pretty thrilling, gory horror movie.

And yet Coogler’s wildest, most ambitious, most creative idea — one fascinating enough to be the plot of a movie all on its own — gets one breathtaking, inventive sequence, and then gets dropped from the movie entirely. There’s a nagging question hanging over more than half of Sinners: What happened to the movie’s biggest and best conceit, and why doesn’t it play more of a role in the story?

[Ed. note: Broad spoilers ahead for Sinners, though this piece is more about what doesn’t happen than what does.]

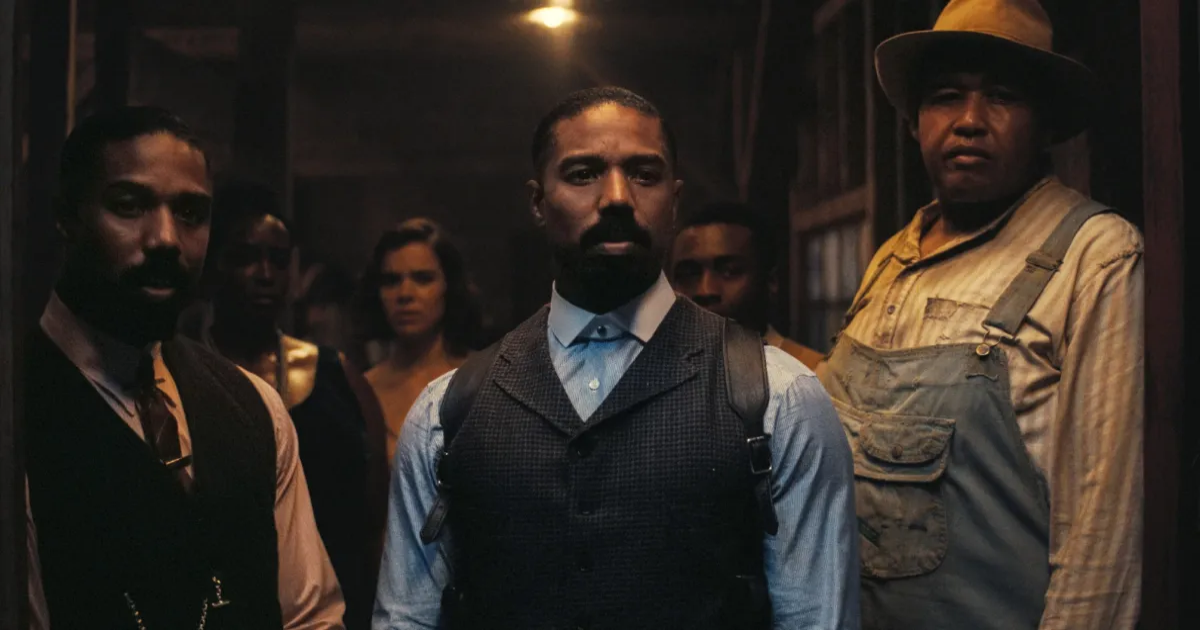

A lot of Sinners rests on the shoulders of Michael B. Jordan as twin brothers Smoke and Stack, aka “the SmokeStack twins.” They’re a pair of sharp-dressing gangsters who left their Mississippi hometown for the criminal big leagues of Chicago, wound up working with Al Capone (a story they unfortunately don’t tell, and only allude to), then returned home with a truck full of stolen booze and a satchel full of money, both of which go into their dream of opening their own juke joint: a business owned by and catering to the Black community. Part of their setup involves bringing in their cousin Sammie (R&B/gospel artist Miles Caton), a preacher’s son and blues prodigy, to perform at their opening.

Sammie, we’re told in voice-over, is one of a rare strain of musicians who’ve emerged over the course of what seems to be thousands of years and across every country and continent. These special talents make music so powerful that it connects them to spirits from the past and the future. And when Sammie finally plays at the club, with an original number called “I Lied to You,” we get to see what that means through one staggeringly emotional sequence.

African tribal dancers, an Afrofuturist soloist with an electric guitar, a ballet dancer, a record-scratching hip-hop DJ, twerking modern-era clubgoers, Chinese opera performers and more all appear one by one, dancing and playing among the crowd, performing alongside Sammie. And composer Ludwig Göransson merges Sammie’s blues song with hip-hop beats, a house-music line, African drumbeats and chants, and a range of modern instruments as the song sprawls out.

It’s a wild frenzy of a sequence, suitable for such a wild idea. Except that Sammie’s ability simply never comes up again, for the rest of the movie. It isn’t pertinent to the plot, and he doesn’t appear to ever be aware of it or learn anything more about it. We get the amazing promise of that sequence, and then that’s it.

Sammie’s power is in theory the hook for Sinners’ vampire element: Irish vampire (and singer, and guitarist, and apparent music-lover) Remmick (Jack O’Connell) enters the story because Sammie’s performance of “I Lied to You” calls to him. He’s familiar with power like Sammie’s, and wants to claim Sammie and his talent so he can summon up the spirits of his own long-dead kin.

With an ability this rare, this powerful, and this inherently cinematic, it seems obvious that Sammie is going to have some central role to play as Remmick and his brood descend on the SmokeStack brothers’ juke joint. Given the movie’s understanding of vampires as malign spirits encased in dead human bodies, genre fans in particular might anticipate a finale where Sammie calls up the spirits of Remmick’s victims to battle him, fighting a supernatural power with a supernatural power. Or it’d be easy to visualize a sequence where Sammie does exactly what Remmick demands and summons his dead kin — who call Remmick back to the grave where he belongs.

There are any number of ways the power to bind together music from throughout history might play into the storyline we’re given: as a way to distract and mesmerize Remmick and his followers until the sun comes up, or to force him to understand what a hellish creature he’s become. We’re even told at the beginning of the movie that this kind of uniting musical power helps settle spirits, in what seems like obvious foreshadowing about Sammie’s need to understand the place and purpose of his music, and learn how to use it to put a troubled world at ease.

Instead, the solution to Remmick’s threat is a lot more mundane, accidental, and frankly less interesting. The climactic combat has some resonance with the rest of Coogler’s themes in Sinners, given how it touches on Sammie’s musical instrument of choice, where it came from, and what it means to him. It’s true that there’s an innate symbolism in his guitar being his salvation, and in it being destroyed in the process, and in his refusal to let go of it afterward, no matter how his preacher father prays over him and begs him to drop it.

But having the guitar accidentally save him takes a lot of the power out of Sammie’s hands, and draws a lot of the intrigue out of his actual talent. A story that seems to be about the Smokestack twins’ obvious personal and financial power — their confidence and ease with violence, their elevated place in the community and its legends — giving way to Sammie’s softer and more creative power turns out to just be a story about the twins’ dreams falling apart, with Sammie as one witness among many. That lack of resolution or even meaning for Sammie’s fascinating power makes Sinners feel incomplete and even distracted by all the other themes, ideas, and subplots competing for attention.

Sinners even includes a lengthy mid-credits epilogue, set in 1992, that feels like an obvious chance to bring the movie back around to where it began, with that voice-over explaining Sammie’s connection to the musical continuum. And even that epilogue misses the chance to make his power meaningful.

[Ed. note: OK, real, significant spoilers ahead.]

In the mid-credits sequence, a much-aged Sammie (now played by blues legend Buddy Guy) is playing in a club, clearly nearing the end of a successful and celebrated career. After the show, he sits at the bar as Stack and his girlfriend, Mary (Hailee Steinfeld), stroll in to meet him, looking just as they did in 1932, apart from their garish ’90s clothing. Stack treats Sammie kindly, like an old friend, and offers to vampirize him to preserve his fading life. When Sammie rejects that option, Stack asks Sammie to play some good old acoustic Delta blues for him.

We’ve seen at this point what vampires in the Sinners setting are like — how cruel and voracious they are, how easily they lie, how easily they kill, how physically unstoppable they can be compared to fragile humans. There’s no reason to believe vampire Stack and Mary are any different, apart from the fact that they don’t casually kill the only other human present. (They may have gotten the bouncer, though — that’s left unclear.) For a moment, it seems like Sammie, clearly older and wiser and having grown into himself and his talent, might bring back that old power, either to end the threat Stack and Mary arguably pose to the world, or just to summon up everything they once shared and have now lost.

It feels like such an obvious coda, especially given what Remmick expressly wanted and couldn’t get: the chance to see his old friends and loved ones again through Sammie’s power. And the setup seems like such an obvious excuse for a sequence as beautiful and heartfelt as that mid-film one-shot scene, except this time with Sammie consciously calling up his own old friends and loved ones for the only other people left who might remember them.

But no, Sammie just sings one verse of a blues song about a woman who doesn’t care about him, nothing magical happens, and Stack and Mary move along. It’s a bittersweet ending, meant to communicate the importance of moving on to whatever comes after a life well lived. And it comes with some powerful commiseration between Sammie and Stack about the last time they saw each other, and why, in spite of everything terrible that happened that day, it was the best day of both of their lives. It isn’t a bad ending at all, and it comes with thoughtful intentions.

But it still raises the question of why Coogler came up with such a beautiful, memorable idea and expressed it in such glorious style, only to abandon it halfway through the movie. Sammie’s power isn’t the only idea Sinners raises and doesn’t have time to explore: The movie is packed with characters and incidents, with relationships and history and conflict both immediate and historical, both personal and institutional. There’s so much going on in this film, as if Coogler was trying to ensure he didn’t miss out on any chances to explore a setting and situation he loved, and to tap into so many aspects of his own family history.

But it still feels like a strange omission: a kind of Chekhov’s gun that gets fired once, into the air, then never touched again. Here’s hoping Sinners does well enough that Coogler can return to the film’s most intriguing idea if he ever wants to and explore it in more depth. A concept with such infinite potential shouldn’t be relegated to one finite scene, no matter how beautiful that scene actually is.

Sinners is in theaters now.

See More: