This post contains spoilers for Sinners.

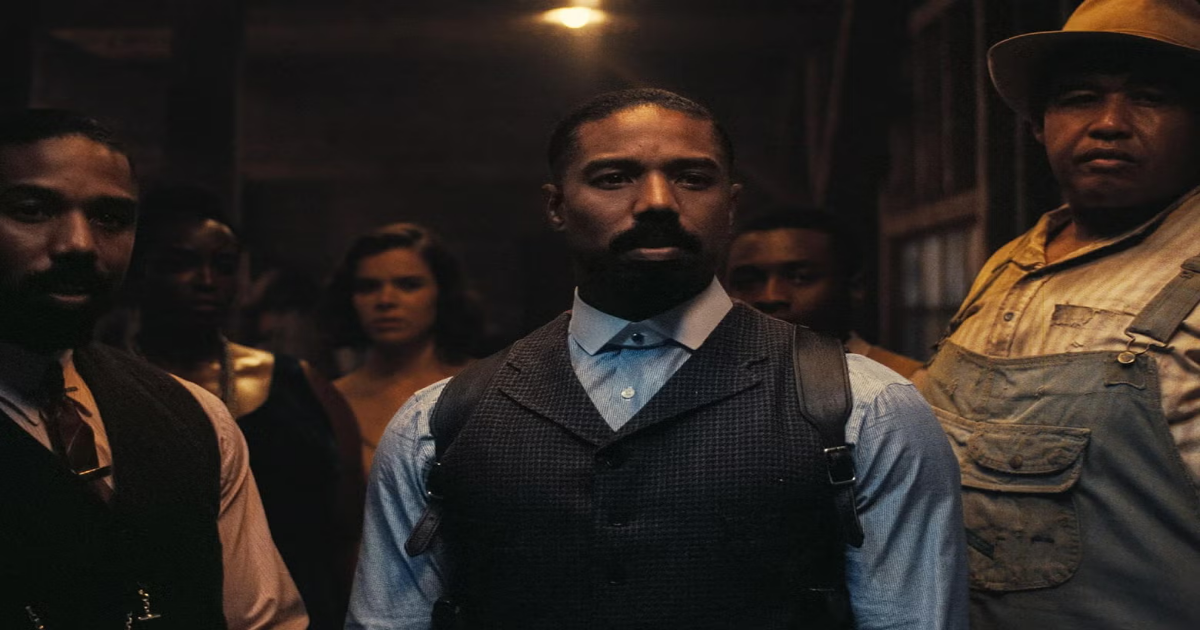

Sinners, the latest feature film from Black Panther director Ryan Coogler, is a different kind of vampire movie. Set in 1932, the story takes place over the longest 24 hours one might imagine in Clarksdale, Mississippi. It follows the Smokestack twins—aptly named Smoke and Stack (both played by Michael B. Jordan, in his fifth collaboration with Coogler)—who, at the start of the movie, have just arrived back in the Delta after leaving to fight in World War I and then sojourning in Chicago, where they worked for Al Capone. Now they’re back home—more willing to face “the devil [they] know” in the Jim Crow South than the ones they don’t in Chicago—with suspiciously acquired bags of money. They fork over a sum of cash to a white man for the old sawmill, intending to turn the property into a brand-new juke joint that very night. The first half of the movie sees the twins mine their dormant hometown connections to procure the musical talent for their business, while also running into some old flames.

The second half of the film is where Sinners’ undercurrent of supernatural horror comes out at full blast—and where Coogler’s proven interest in exploring racial politics is brought to the fore. A dark force is teased in the movie’s prologue, which opens with a legend of certain individuals who possess the gift of making music that blurs the line between life and death—a power that can heal, but also attract evil. That so-called evil, it turns out, refers to vampires. We see the vampire Remmick (Jack O’Connell) turn a white couple—implied to be members of the Ku Klux Klan—into members of his nightwalking ilk. In the evening, when the twins’ cousin Sammie (Miles Caton), a musical prodigy, starts to play at the juke joint among a throng of gyrating, immaculately moisturized, Black bodies, we see the history and future of Black music—African drums and dancing, ’80s hip-hop and breakdancing, Prince-like electric guitars, modern-day trap music and twerking—comingling on the dance floor. It’s when these lines between life and death, between future and past generations, become undefined that Remmick shows up to the party with his two new recruits. They turn any poor soul who wanders out of the juke joint—which, due to a crisis inside that ends the party early, is almost all of them—into members of their red-eyed, bloodsucking clan. By the time the few remaining characters inside realize the unnatural transformation occurring outside, the vampire’s carnage has already taken most of the partygoers, including Stack and his former lover Mary (Hailee Steinfeld), leaving the vampires with one classic request: Invite us in.

One reading of this film is that the villains are the vampires: Just picture, three bone-chilling white vampires standing at the entrance of this Black establishment, asking to be let in. But that reading ignores the specificities Coogler imbues his portrayal of the undead with, leaving the audience with a more nuanced message. A less ambitious movie would build its binary of good and evil off the chilling imagery of the vampires at the door, simplifying the matter to “vampires = white predators” and “humans = Black victims and heroes.” Thankfully, Coogler is not that kind of filmmaker, and Sinners is not that kind of movie. If the movie’s white, bloodthirsty monster is not the true villain of Sinners, then who—or what—is? The answer lies in the film’s interrogation of the lengths you’d consider going to escape structural torment. The greatest evil here is white supremacy, the system of structural racism and bigotry underlining all aspects of life in 1930s Mississippi.

In Coogler’s supernatural vision, the vampires are ultimately presented in a sympathetic light, expressing solidarity in grief and loss with the preyed-upon Black characters—furthermore, there’s an even more sinister power to fear in this film. Remmick positions himself as an ally to the oppressed, rather than yet another oppressive force, by revealing a worse evil than himself. He reveals to Smoke and the others that the white man who sold the twins the sawmill is the leader of the local KKK chapter, who—despite the twins’ asserting that their money must also buy them protection from the Klan—plan to show up the next morning, burn down the property, and murder anyone left inside. Of course, this could just be a fearmongering tactic—if Remmick weren’t proven right in the end.

But Sinners’ humanization of Remmick doesn’t stop there. The fact that Remmick is Irish—as signified by his slight accent and by a truly spine-tingling Irish folk number he leads the freshly turned vampires in performing—is key. Irish people in America were not considered racially white in the way that they are today; they have a history that shares similarities with that of Black people, involving colonialization, religious persecution, and more. Thus, Remmick’s plea to those still inside the juke joint is realistic: Black people are never safe from persecution. They can stay among the mortals, where their money is no good to the ruling white class, where they can be conned or lynched at a moment’s notice—or they can join him and his cultish community, where former KKK members now commune with their fanged Black and Asian brethren. It’s an alternative in a world with no truly good options. Is it a life of darkness and destruction? Sure. But it’s a life, nonetheless. Remmick’s opening pitch to get the Black folk left inside the juke joint to join him, then, is not a threat, but a call for solidarity.

The vampires are shown goodwill in other ways as well, complicating some critics’ reading of the creatures as—in Variety critic Owen Gleiberman’s words—“extensions of the racist white culture that wants to stop the party.” For instance, Remmick and Mary—who is multiracial, and passes for white, but grew up as a member of this Black community—seek comfort in Black gatherings, a pull that’s rooted in their shared histories. The vampires are attracted to the legendary musical gift because, when the lines between life and death blur, the eternal undead can finally reunite with those they lost. Remmick wants Sammie because, as he puts it, “I wanna see my people again.” It’s messed-up logic, certainly; at worst, as Empire’s Helen O’Hara claims, these “attempts to humanise” Remmick “as another victim of colonialism and forced religion don’t really work when he’s now attempting the same appropriation.” But Coogler at least presents a more complicated conundrum in a genre that can easily be black and white. To say that the Black people facing the vampires at the door of the juke joint are between a rock and a hard place is an understatement. Even though Remmick’s plea means death of a certain variety, it also promises a future—one outside the boundaries of life and death, but also outside the boundaries of systemic hate.

This conclusion doesn’t just come from a sympathetic view of certain white characters; it also stems from Sinners’ final moments. The biggest clue about Sinners’ racial politics is in Smoke’s last stand, which occurs not against the vampires, but against the white Klan members who arrive the next morning. Tellingly, the movie’s final bullet goes into the Klan leader. And in case that wasn’t enough evidence about the film’s message, there’s also the midcredits scene (one of two) that jumps forward to the ’90s and reveals, in part, that Stack survived that bloody night as a vampire, one of only two Black people to make it out alive (of sorts). In the modern day, Stack admits he’s not entirely free—but who in Coogler’s tale even is? Stack misses his brother, and the sunlight, but hell, at least he’s still here. That in itself is a kind of salvation.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.