Este artículo estará disponible en español en El Tiempo Latino.

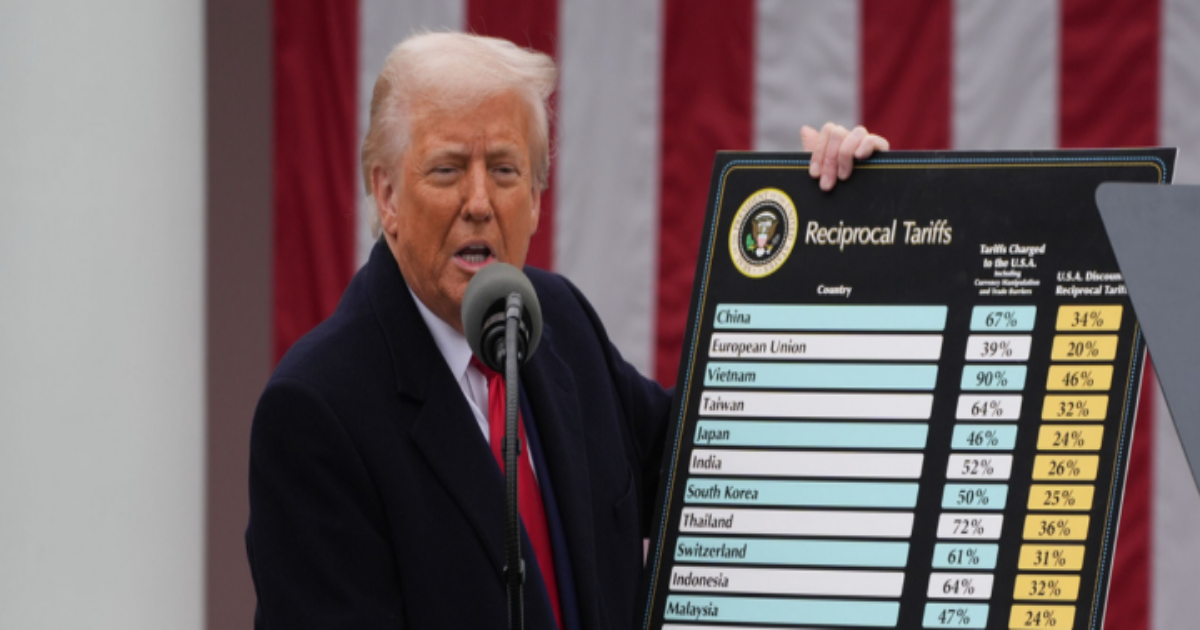

In his Rose Garden announcement of sweeping new “reciprocal tariffs,” President Donald Trump held aloft a misleading chart that claimed to give a breakdown of the tariffs other countries charge the U.S. and the corresponding tariff that the U.S. will now impose against those countries.

“Reciprocal. That means they do it to us and we do it to them,” Trump said in his April 2 speech. “Very simple. Can’t get any simpler than that.”

Trump said the U.S. would begin charging a “minimum baseline tariff of 10%” on all imported goods. But he said the U.S. would also tariff countries at a rate equal to half of tariff rates that countries charged for U.S. goods “including currency manipulation and trade barriers.” That, according to Trump’s chart, would mean tariffs of 50% on imports from some countries.

The first column next to the list of countries purported to represent “Tariffs Charged to the U.S.A.” as a percentage. A cursory look revealed, however, that the percentages are far higher than the average tariff rates published by the World Trade Organization. Smaller print under the “Tariffs Charged” heading notes — as Trump did — that the figures include “Currency Manipulation and Trade Barriers.” Those last two factors are harder to quantify, but it turns out that’s not how the White House arrived at its figures anyway.

“You see the numbers, the numbers are so disproportionate, they’re so unfair,” Trump said.

According to a fact sheet provided by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the reciprocal tariffs were “calculated as the tariff rate necessary to balance bilateral trade deficits between the U.S. and each of our trading partners. This calculation assumes that persistent trade deficits are due to a combination of tariff and non-tariff factors that prevent trade from balancing. Tariffs work through direct reductions of imports.”

USTR said that while computing trade deficit effects for every country “is complex, if not impossible, their combined effects can be proxied by computing the tariff level consistent with driving bilateral trade deficits to zero.”

To approximate that, USTR said it divided the size of a country’s trade imbalance with the U.S. in goods by how much America imports in goods from that nation.

Take the European Union, for example. The chart lists its tariffs charged for U.S. imports (again, including currency manipulation or trade barriers) as 39%. Trump said the U.S. would charge countries half of what they are charging the U.S., because charging the full reciprocal amount “would have been tough for a lot of countries.” So in the case of the EU, the “USA Discounted Reciprocal Tariffs” is 20%, the chart states.

According to the World Trade Organization, the EU’s trade-weighted average tariff rate is 2.7%. Trump also noted that European countries charge a value-added tax of about 20% — it varies by country but that’s roughly accurate. But those taxes are levied on imports as well as domestic production, so the VAT does not provide any trade advantage. In any case, neither of those numbers factor into the White House’s math.

How does the White House arrive at 39%? In 2024, the U.S. goods trade deficit with the EU was $235.6 billion. That year, the U.S. imported $605.8 billion worth of goods from the EU. So, $235.6 divided by $605.8 is 38.9%, or, rounded up, 39%.

Economists told us that’s not a legitimate way to calculate reciprocal tariffs for countries.

“Those listed numbers are simply not tariffs, but some other made-up measure based on a formulaic trade deficit calculation,” Kimberly Clausing, a nonresident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, told us via email. “In almost every instance, countries’ true trade barriers are far, far lower.”

“This is not a legitimate way to calculate trade barriers, and the vast majority of subject matter experts (I would wager >99% of international economists) would reject this methodology as profoundly flawed,” Clausing said.

“For example,” she said, “imagine you have completely free trade with an island that produces mangos but lacks sufficient income to buy US goods. The US buys $100 in mangos and sends only $20 in exports. This would imply a tariff rate of 40% by the Trump method, (80/100 divided by 2), but the imbalance of trade represents only the fact of distinct comparative advantage in trade, not any trade barriers.”

Or, as the New York Times put it, “The difference between exports and imports doesn’t necessarily reflect trade barriers; Americans may simply want to buy more stuff from, say, Japan than the Japanese want to buy from the United States.”

“The Trump administration’s calculations are a fundamentally nonsensical way to calculate ‘reciprocal’ tariffs,” Erica York, vice president of federal tax policy at the Tax Foundation, told us. “Absolutely none of the factors the White House purports to be looking at, like tariffs, non-tariff barriers, or other unfair practices, factor in to the tariff rate they calculate in any way. They are invented numbers that have zero relationship to real policies.”

William Reinsch, senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a former president of the National Foreign Trade Council, concurred.

“We do not believe it is an appropriate or accurate measure of trade barriers,” Reinsch told us via email. “We believe their methodology basically has nothing to do with reciprocal tariffs as the administration had previously discussed. The most charitable interpretation of what they are saying is ‘this is the tariff rate that would be necessary to balance bilateral trade with each partner.’”

Countries with which the U.S. has a trade surplus – such as the U.K. and Singapore – are still listed on the chart as charging 10% tariffs.

According to York, if the aim is to balance trade with every country, these proposed tariffs won’t work.

“Tariffs will not reduce the US trade deficit because tariffs, either through their effects on the US dollar or through retaliation, will also reduce US exports,” York said. “That’s a result borne out in economic literature, and in recent US experience with the 2018-2019 tariffs.”

Economists also noted that the White House equation focuses only on goods, and ignores trade in services, where the U.S. enjoys a trade surplus.

“That skews the results. A lot,” Clausing, of the Peterson Institute, told us. “The US has a comparative advantage in services, and this ignores our substantial trade surpluses in that sector.”

“Excluding services is simply wrong and doesn’t give the full picture,” Stuart Malawer, a professor emeritus of policy and government at George Mason University, told us via email.

U.S. Trade Representative Fact Sheet

The USTR fact sheet on the reciprocal tariff calculations cited a handful of academic studies, but when we reached out to the authors of several of them, they balked at the Trump administration’s conclusions.

“The tariffs charged to the USA column certainly does not represent legislated tariffs faced by the US,” Anson Soderbery, an economics professor at Purdue University and author of the research paper “Trade elasticities, heterogeneity, and optimal tariffs,” told us via email. “Those are much smaller than reported and take into account bilateral agreements (e.g., USMCA, WTO preferential duties, etc).

“If they are using the USTR formula proposed this morning to adjust those numbers, I am even less sure how to go about evaluating what they mean,” Soderbery said. “That is, suggesting trade imbalances are only due to trade barriers is not founded in any economic theory or methodology. And, further suggesting the reductionist formula exports-imports/imports can be used to back out all trade barriers and equivalent tariff rates is misguided.”

Ina Simonovska of the University of California, Davis, and co-author of “The elasticity of trade: Estimates and evidence,” told us via email, “The formula that the administration uses is correct under the assumption that the objective is to arrive at a zero bilateral trade balance with a given trade partner, holding fixed any other effects.” But there will be other effects, she said, including “the changes in exports that would occur due to the domestic price increases caused by the tariff as well as changes in trade flows with other trade partners than the one that the tariff targets. … These effects are harmful so they would result in a lower optimal tariff compared to the reported one” in the White House chart.

The USTR fact sheet also cites as a reference for its estimates a paper published in American Economic Review, “The Long and Short (Run) of Trade Elasticities.” One of the authors of that paper, Andrei Levchenko, a professor of international economics at the University of Michigan, told us via email that the “elasticity estimate” in the paper and used by the USTR “should not be directly applied in this tariff calculation.”

“The key reason is that the concept of the trade elasticity holds everything else constant,” he explained. “In practice, everything else will not be constant. In particular, US exports could change. That can come from a variety of channels, but one important one is tariff retaliation by trading partners. If a trading partner puts tariffs on US exports to it, they will fall, (at least partially) un-doing the impact of lower imports on the trade deficit.

“Beyond this, there are many other ways in which the change in US imports and exports will differ from the formula that directly applies a partial equilibrium trade elasticity,” he said. “For example, trade elasticity estimates do not account for any impact of the change in tariffs on wages, prices, exchange rates, and the stock market. Those can go in different directions depending on the country, the product, the production technology used, etc. For small tariff changes on individual products from individual countries, these changes might be small and could reasonably be ignored. However, the change in imports and in the bilateral trade balance implied by the partial equilibrium trade elasticity is likely to be

unreliable when the tariff change is large and comprehensive (covering all goods), as is the case today.”

Repeated Claims

Trump got other things wrong in his tariff announcement. He continued to wrongly frame his tariffs as a way to raise “trillions and trillions of dollars to reduce our taxes.” Tariffs are a tax. And because U.S. importers pay the tariffs, and often pass at least some of their increased costs onto consumers through higher prices, tariffs are considered to be regressive taxes, affecting lower-income households more than others as a percentage of income.

A Tax Foundation analysis projected that the tariffs announced on April 2, combined with earlier tariffs announced by Trump, would raise nearly $3.2 trillion in revenue over 10 years. But the tariffs would also reduce Americans’ after-tax income, amounting to “an average tax increase of more than $2,100 per US household in 2025,” the Tax Foundation said.

Trump also repeated false or misleading trade claims that we’ve already covered.

He said Canada “imposes a 250 to 300% tariff on many of our dairy products,” referring to rates that would only be charged if U.S. exports to Canada ever exceeded predetermined quotas. He said tariffs made the U.S. “proportionately the wealthiest it has ever been” between 1789 and 1913, even though real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product per capita is many times higher today than it was more than a century ago. And he claimed that during his first term he “took in hundreds of billions of dollars” from tariffs on China, which he said “never paid 10 cents to any other president.” But the U.S. has long collected billions from customs duties on Chinese imports — and the tariffs are paid by U.S. importers, not China.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.